Chapter 4—Slow Flight, Stalls, and Spins

Table of Contents

Introduction

Slow Flight

Flight at Less than Cruise Airspeeds

Flight at Minimum Controllable Airspeed

Stalls

Recognition of Stalls

Fundamentals of Stall Recovery

Use of Ailerons/Rudder in Stall Recovery

Stall Characteristics

Approaches to Stalls (Imminent Stalls)—Power-On or Power-Off

Full Stalls Power-Off

Full Stalls Power-On

Secondary Stall

Accelerated Stalls

Cross-Control Stall

Elevator Trim Stall

Spins

Spin Procedures

Entry Phase

Incipient Phase

Developed Phase

Recovery Phase

Intentional Spins

Weight and Balance Requirements

STALLS

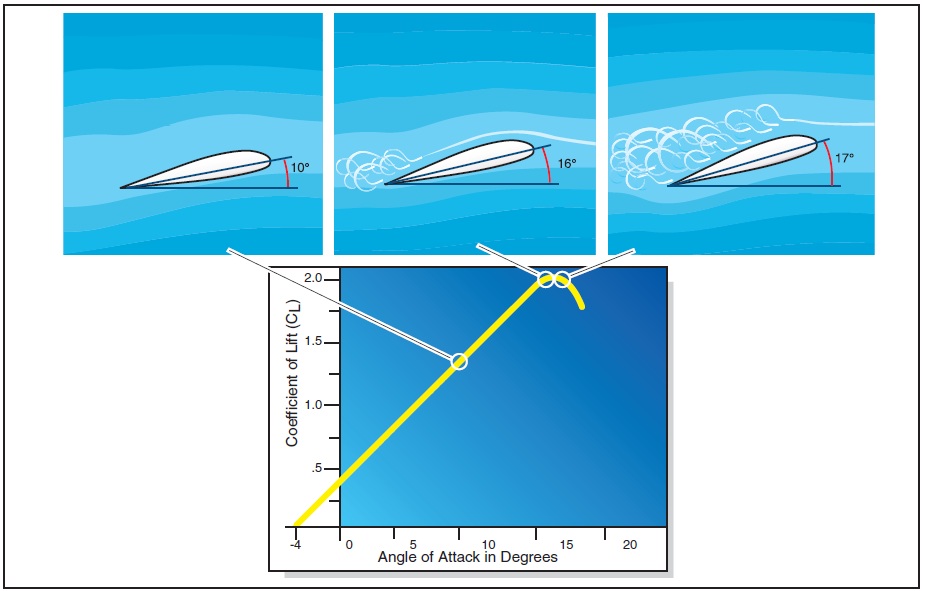

A stall occurs when the smooth airflow over the airplane’s wing is disrupted, and the lift degenerates rapidly. This is caused when the wing exceeds its critical angle of attack. This can occur at any airspeed, in any attitude, with any power setting. [Figure 4-2]

Figure 4-2. Critical angle of attack and stall.

The practice of stall recovery and the development of awareness of stalls are of primary importance in pilot training. The objectives in performing intentional stalls are to familiarize the pilot with the conditions that produce stalls, to assist in recognizing an approaching stall, and to develop the habit of taking prompt preventive or corrective action.

Intentional stalls should be performed at an altitude that will provide adequate height above the ground for recovery and return to normal level flight. Though it depends on the degree to which a stall has progressed, most stalls require some loss of altitude during recovery. The longer it takes to recognize the approaching stall, the more complete the stall is likely to become, and the greater the loss of altitude to be expected.

PED Publication